‘We Grew Up at Furman’

Someone had called security.

The reason for the concern? A teenage girl had shown up with her mother, her voice teacher, high school principal, and a member of the Black fraternity Omega Psi Phi. The group had come to support the girl in her crucial moment – her voice audition before Furman’s music faculty.

The teen’s name was Sarah Reese, and she had an appointment to be there. But no one was expecting a Black student.

“Furman had no idea who was coming to dinner,” said Reese, who grew up in rural Pelzer, South Carolina, and graduated from Furman in 1971.

“Here was this little brown girl who had no idea of the magnitude of this. It means even more to me now than it did then that people had fought for me to have an audition.”

Reese would become a world-famous opera singer, making her New York debut in 1981, and performing with some of the world’s most famous orchestras and conductors, becoming the principal artist with the New York Metropolitan Opera and artist-in-residence at the Opera Company of Boston.

But first, Reese, in the course of earning her music degree, would do the solitary, heavy work of forging racial progress in Greenville, South Carolina.

‘Some kind of lonely’

Reese was one of Furman’s first Black students, her time overlapping with Joseph Vaughn’s, Furman’s first Black undergraduate, after the university desegregated in 1965.

Reese, Vaughn ’68 and Lillian Brock Flemming ’71, another Black student, were “the three musketeers.”

But their strong bond was not enough to shield Reese from the stares of white students, the insults from a professor (“nincompoop”), and the refusal of students to room with her after her first roommates – progressive white students – had graduated at the end of her first year. Reese and her white roommates had been close, attending Martin Luther King’s funeral together in Georgia, even sleeping on the ground during the trip. After her roommates graduated, however, Reese was left to live in a room alone next to the house mother’s quarters.

“It was some kind of lonely when Lillian wasn’t on campus or Joe was busy,” said Reese. “Most of the time, 95% of the time, you’re sitting there alone,” she remembered. “And nobody wanted to sit with you. Or they’d kind of sit with you and leer.”

There was also the “brick in the hat.”

“Cowards,” said Reese, would run by and throw bricks at Reese and the other Black students’ heads in the dark when the friends occasionally gathered in the Rose Garden in the evening.

“Those were the times of our society, not just Furman,” said Reese. “It was a microcosm of our society. At the same time, the education I got from Furman, musically, I could compete with anybody anywhere, and academically.”

A special bond

In the moments when she was bent by the weight of the time, it was Vaughn who stood her back up.

“Joe was always there, always,” she said. “If I said, ‘I am going to quit, I can’t stand it any longer,’ he’d say, ‘You have to (stay). You’re not going anywhere.’”

Vaughn was their big brother, their rock, protector and “papa.” In 1968, after the Orangeburg Massacre, the three of them demonstrated in downtown Greenville, a march organized by Vaughn, and were stunned after a man tried to run them over with his car.

On ordinary days, Flemming and Reese would go to football games to cheer on Vaughn, a cheerleader, who made up his own infectious cheer and never hoisted the white female cheerleaders.

‘A luscious voice with dramatic bite’

Reese was, simply, a star.

She was “a young soprano who has it all – a luscious voice with dramatic bite and astonishing coloratura agility, disarmingly natural musical instincts and a compelling stage presence,” concluded The New York Times in September of 1981.

Reese in “The Legend of the Invisible City of Kitezh and The Maiden Fevronia” in April, 1983. Music by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. Opera Company of Boston production photographs courtesy of Elliot J. Cohen. Photo: Milton Feinberg.

Nearly two years later, the Times described her as “a wonderfully pure, sure soprano that seemed to grow in beauty and confidence as the afternoon progressed,” as Fevronia in Rimsky-Korsakov’s “Legend of the Invisible City of Kitezh and the Maiden Fevronia.”

In November of 1983, the Times said Reese’s role in Puccini’s “Turandot” was “as Puccini envisioned her.”

Moreover: “Her melodic lines were fluid and supplicatory, but no less assured or compelling in her fine accusatory aria of the final act; earlier, ‘Signora, ascolta,’ was touchingly compassionate,” continued the Times.

“Miss Reese’s performance seemed much larger than its deliberately small-scaled sensitivity.”

She was the featured soloist on the 1993 Grammy Award-winning recording, “Prayers of Kierkegaard” with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and made her Carnegie Hall debut with The American Composers Orchestra in 1995. Reese performed roles in Switzerland, England, France, Monte Carlo, Italy and Russia, and traveled to Toulouse, Strasbourg, Dusseldorf and Cologne with the Festival Orchestra of Sofia, Bulgaria, as the soprano soloist in Verdi’s “Requiem” and Beethoven’s “Ninth Symphony.” She also performed with the BBC Symphony Orchestra at the Royal Albert Hall in London.

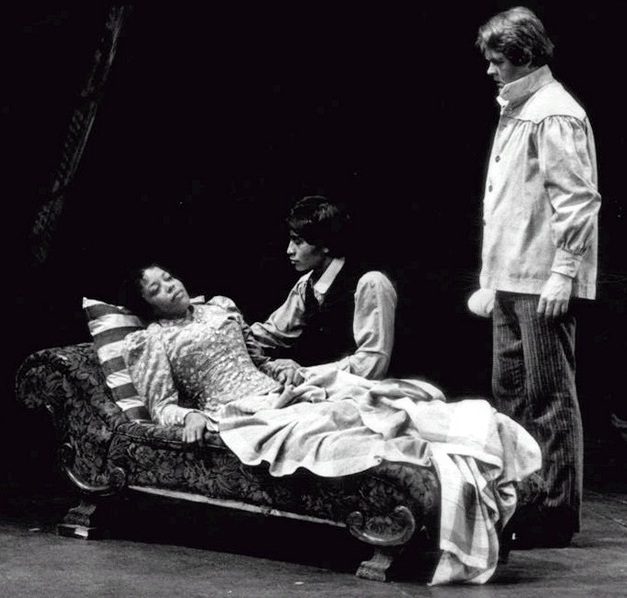

Reese in “La Boheme” by Giacomo Puccini with Noel Velasco and Lenus Carlson in 1982. Photo: credit: Milton Feinberg; Opera Company of Boston production photographs courtesy of Elliot J. Cohen.

Homecoming

In her later years, Reese returned to rural South Carolina. She taught music at Pendleton High School and chaired the school’s fine arts department. In 2013, she was named a Yale Distinguished Music Educator, and in 2014, Furman conferred upon her a Doctor of Humanities.

In 2020, Reese and Flemming attended the homecoming basketball game at the invitation of Furman President Elizabeth Davis. Reese cried when she heard the national anthem.

“We just wept to see so many African Americans joyfully frolicking with other human beings, without duress,” she said. The sight would have been unimaginable when she was a student.

Today, Reese fills with emotion when she speaks of her experiences at Furman.

“I love Furman. Furman is the reason,” she said. “We grew up at Furman.”

Editor’s note: In celebration of Joseph Vaughn Day at Furman University, we are recognizing the experiences of other Black alumni who enrolled soon after the university integrated in 1965.