By the work of their hands

In his now famous commencement address at Stanford University, Steve Jobs said, “You’ve got to find what you love . . . the only way to do great work is to love what you do.”

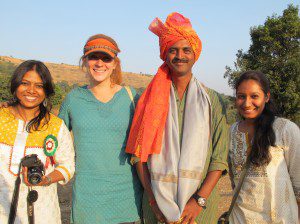

For many, it takes stepping outside their comfort zone to find what really inspires them. Earth and Environmental Sciences graduate Virginia Batts ’11 took a giant step into India, “land of a thousand languages” to follow her passion.

As winner of one of only 10 Compton Mentor Fellowships awarded to students across the nation in 2011, the Nashvillian paired her interest in India’s history and culture with her concern for land and water resources.

As part of her fellowship application, Batts approached WOTR, Watershed Organization Trust, based in Pune, India, a non-profit NGO that works with vulnerable rural villages to help them adapt to climate change. She teamed with WOTR mentors to compile a “how-to” manual for a participatory mapping process which bridges local knowledge of terrain together with topographical and other geophysical information.

In P3DM, or Participatory 3-D Modelling, the idea is to craft a scaled relief model of the landscape showing features most important to locals—disaster prone areas, protected areas, village dwellings, temples, streams and forests, for instance. The purpose? To ultimately put the villagers in the driver’s seat, so to speak, when it comes to dealing with the effects of climate variability, so they may reach a state of economic and ecological resilience.

The handbook, “CoDriVE (Community Driven Vulnerability Evaluation) Visual Integrator for Climate Change Adaptation,” is the offspring of Batts’ and WOTR’s work in villages where livelihoods are most directly and severely impacted by shifting climate.

Once completed, the cooperatively constructed relief map generated through CDVE remains in the community, serving as a tangible tool for assisting in sustainable agriculture practices, water budgeting and irrigation, diversification of livelihoods, and identifying alternative energy sources, among other uses.

While participatory mapping has been around since the late 80s, Batts focused on retrofitting P3DM into WOTR’s climate change adaptation initiative in at-risk villages in the states of Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, and Madhya Pradesh. To date, CDVE has been implemented in five different villages. Of those, Batts participated in two of the mapping workshops.

CDVE spans the often large gap between indigenous people, development workers, and policy makers. Historically, people in developing countries haven’t had a seat at the table when it comes to voicing concerns over land use. By getting buy-in from the local community at the grassroots level, whole villages are better prepared to take ownership of development issues and take steps to prevent or mitigate the effects of climate change.

Says Batts, “No governing body or development official knows the land better than the villagers. With CDVE, that knowledge is transposed onto something the community creates, in a workshop where lines of communication between participants and facilitators remain completely open.” Batts says the transparent nature of the process goes a long way toward building relationships and trust, and lays the foundation for future work.

After project objectives are clearly articulated among facilitators (like WOTR) and community members, and supplies are gathered, the model is ready to be constructed—a process that takes anywhere from three to seven days. Objectives might be to map land uses in the region, locate biodiversity hotspots, landslides, or map sources of water, for example.

Using readily available materials—cardboard, newspaper, paint, glue and yarn—participants go to work on the base map. First, a large topographic (or contour)map is used for reference. With carbon paper, participants trace contours (or elevations) onto cardboard, one contour at a time. This process is repeated on a different sheet of cardboard until all elevation contours have been traced. Once the contour layers are cut and trimmed, the model is ready for assembly.

Like a wedding cake, layer upon layer of cardboard contour cut-outs are stacked onto the base with glue. After the model is completely dry, small strips of paper are applied to the model a la papier-mâché with white acrylic primer. What results is a white, blank canvas depicting the hills and valleys of the region.

At this point in CDVE, the model is ready for demarcation, the stage where indigenous knowledge comes into play, and where the model’s objectives should be revisited to keep stakeholders on the same page. Penciled-in features such as roads, bridges, and rivers, village boundaries, conserved forest and farmland are delineated with pins, yarn, and paint.

The completed model isn’t just functional; it’s a work of art. Beautiful and brilliantly colored, the model becomes a valuable planning tool, and represents a source of pride and empowerment for the community as it embodies generations of collective knowledge. And the model’s life is extended through aerial photographs which are transferred to a GIS so the information may be used for further planning.

Batts appreciates the idea that with CDVE, locals are in a better position to adapt to dramatic swings in climate. She says a science and technology-only approach to resource degradation can only go so far. The participatory nature of CDVE helps indigenous communities understand the sources of resource insecurity so villagers can help themselves adapt to conditions like excessive drought and soil degradation.

Batts, who is working on a master’s in water resources science at University of Minnesota, says her experience in India and other places fueled her interest in water resource regeneration. “Water connects everything. When I think about why I study water, I’m reminded that the beauty of the natural world, access to high quality food, and excellent health are essential ingredients to a fulfilling life—and I’m lucky to be able to say I’ve enjoyed them all so far. Water is at the nexus of all three . . . I like the idea that I can potentially make a difference in someone’s life just by redesigning water use and treatment in a way that doesn’t harm the resources of the less privileged nor those of generations to come.”

Learn more about CoDriVE, or download a pdf of the handbook, “CoDriVE Visual Integrator for Climate Change Adaptation: Guiding Principles, Steps and Potential for Use.”