Visualizing Emancipation

The concept seems counterintuitive at first, the reduction of the profoundly individual experience of slaves gaining freedom to bits of data on a digital map. But is it?

Alex Lange ’17 doesn’t think so. As one of 11 students who participated in the University of Richmond’s Visualizing Emancipation Project last spring, he came away with exactly the opposite feeling as he researched information as part of an ambitious attempt to find patterns in the spread of freedom across the South during the Civil War.

“It really is a way of personalizing these stories so it’s easier to access and understand,” Lange, a history major from Nelson, N.H., said.

Liberty didn’t come to all the moment Abraham Lincoln’s pen met paper on Jan. 1, 1863. Emancipation was instead a chaotic, protracted process, and the Visualizing Emancipation Project is an ambitious attempt to humanize the people involved by documenting the moments they gained their freedom and illustrating them on a digital map.

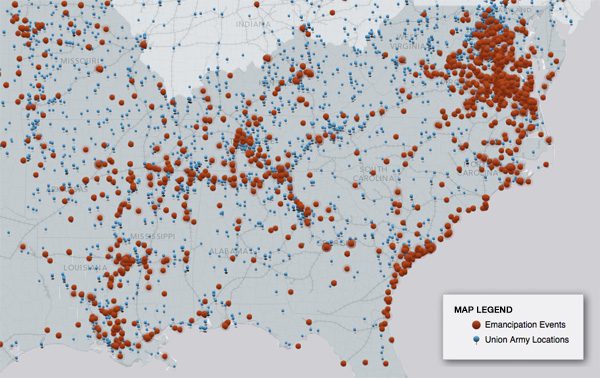

The map’s animation runs from Jan. 1, 1861—three months before the start of the Civil War—until Dec. 31, 1865, nearly nine months after Robert E. Lee’s surrender at the Battle of Appomattox Court House. Along the way, visitors can watch the end of slavery spreading across the landscape in different ways depending on the filter selected.

“It’s really exciting to watch the thing,” Dr. Lloyd Benson, the Walter Kenneth Mattison Professor of History at Furman, said. “If you run the animation you can see these emancipation events starting as soon as the war does and continuing in these waves, and you can see the relationship between where the army is and where and emancipation happens.”

Such a big project requires big data, and Furman students were part of a collaboration with students from Richmond, Millsaps College, and Rhodes College, who worked under a grant from the Associated Colleges of the South scouring multiple sources for emancipation events or other materials related to slavery to add to the database. Lange and his classmates focused on digital editions of the Raleigh (N.C.) Semi-Weekly Standard from the year 1862 at the direction of Benson, who decided this would be a unique direction to take his first-year writing seminar.

“This was a real opportunity in my mind for first-year students to do a really important project in public where the results wouldn’t just be something where the professor would read and give a grade and that would be the end of it, but where a student’s work would actually be a part of this larger thing,” he said. “It takes them maybe an hour per issue, and they look for things where a slave changes status in some way. The whole class together does about a six-month run of newspapers. For each individual student it’s really not that major of a project, but for a dozen students . . . you’ve added 200 events to the database, and it becomes quite an impressive contribution.”

After having Benson as a professor earlier in the year, Lange sought him out again for the writing seminar. It turned out to be a good decision.

“My work focused on looking at primary sources and trying my best to represent that data through my writing,” he said. “I think that’s really important for someone even if you’re not a history major to look at a piece of writing and represent it in a way that’s easily understandable . . . These stories remain untold because people don’t want to put in the effort to access a, say, The Raleigh Weekly Standard that showed up in the 1800s.”

Lange says the age of the internet has fundamentally changed learning history away from memorizing dates, which are now accessible almost instantly, to focusing on bigger pictures. This project is an example.

“That class really helped me analyze trends and sources,” he said.

The most memorable story Lange read involved a group on New England troops getting into a firefight with some Maryland soldiers over whether or not to sell some freed slaves to Cuba (Maryland was against the idea). It wasn’t the only time young people in the year 2014 were shocked by an 1860 mindset.

“All these people would put ads in the newspapers saying if you’ve found such and such, whatever name it was, I’ll give you $20. . . they just really wanted to get their workers back,” Jackson Belcher ’17, a native of Manhattan Beach, Calif., said. “African Americans were not treated as not people. They were treated as things.”

There are reasons it’s uncommon for freshmen to participate in such projects.

“Most first-year, first-semester undergraduates are not trained, advanced historical scholars, so the kind of work that they might be able to do is limited by their experience or really their lack of experience,” Benson said. “But the ingeniousness of this project, which assimilates lots of tiny little individual bits and pieces, is that students can do things that are at their level of skill but then contribute to something that’s organized at a much more complicated, much more analytically rich level.”

And the unique opportunities didn’t end there. In November, Lange and Benson presented their work at the Southern Historical Association’s annual meeting.

“The Southern Historical Association Conference is not the biggest conference of American historians, but it’s one of the major conferences. So to have students presenting at a major conference is itself quite a big deal,” he said. “And the students are collaborating with each other. We have regular phone calls. We did video chats with students at the other schools, and some of them were senior history majors, so I threw them to the wolves and they did really well. But there was a sense of shared camaraderie of the experience of doing the research too.”

For more on the Furman history department, click here.