The unfinished business of integration

Desegregation began on South Carolina college campuses in 1963, but integration has not yet been completed, a civil rights pioneer told a Furman University audience Thursday.

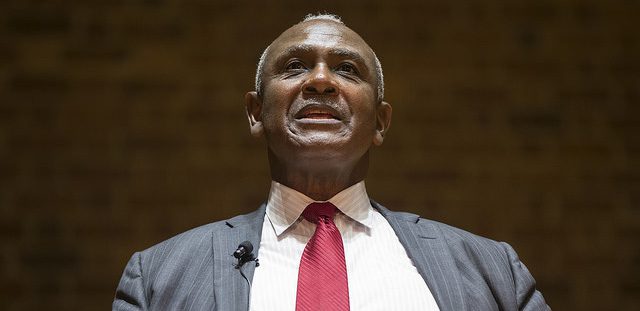

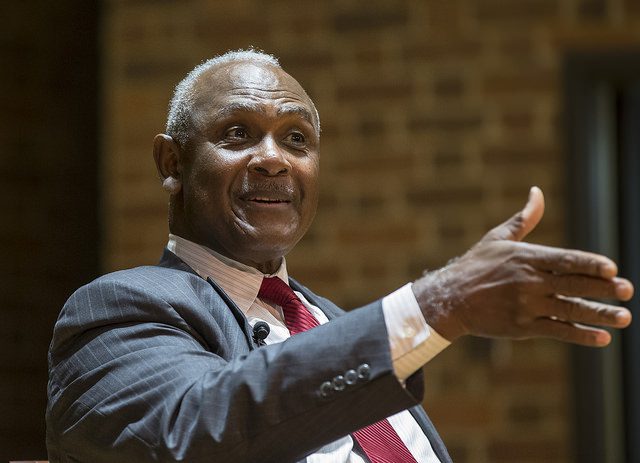

An Evening with Harvey Gantt, one of a series of events to commemorate 50 years of desegregation at Furman, was a conversation between Ron Cox, a South Carolina historian and dean of academic affairs at USC Lancaster and Gantt, a Charleston native and a 1965 graduate of Clemson University.

Gantt was the first African-American to integrate a South Carolina college, an act that came after two years of attempts but was completed peacefully following the turmoil that erupted when James Meredith attempted to enroll in Mississippi.

In answer to a question following the conversation, Gantt said that much has improved since he attended Clemson but that integration is not complete. For example, he often sees students clustered in groups by race.

“That’s a disappointment for me. Fifty years later, I thought I wouldn’t walk into a place like this and there would be a white caucus and a black caucus. Are we really getting a complete education if the circle of people we know are exactly like us?”

Furman history professor Steve O’Neill, Ph.D., introduced Gantt and Cox and discussed the context of the event. Joe Vaughn, a Greenville resident, was the first black student at Furman, enrolling in 1965. He became a campus leader and a teacher following graduation. He died in 1991.

After declaring Gantt an “honorary Furman person,” O’Neill said that “Harvey Gantt will be remembered as long as people write South Carolina history.”

A graduate of Burke High School in Charleston, Gantt participated in counter sit-ins and was arrested while in high school. However, he received a state scholarship that allowed African Americans to receive an equivalent education to one at a South Carolina institution as long as it was at an out-of-state university.

Gantt, who attended Iowa State and graduated with honors from Clemson and received a master’s degree from MIT, served on the Charlotte, N.C., city council and served two terms as its first African American mayor. He also founded Gantt Huberman Architects in Charlotte.

Cox began the conversation by saying he grew up in Washington, D.C., and remembers “the last vestiges of Jim Crow.” When he asked his parents about that time, he said they replied they didn’t think about the injustices because it was the way things were.

Gantt said that segregation wasn’t a major factor in his early life. He said he had a wonderful childhood in “a salt-of-the earth, working-class neighborhood” in Charleston where he played stick ball in the streets and shot marbles in the front yard.

“But there were curiosities and questions we would raise. Why we walked past the white elementary school to the black elementary school. Why we didn’t use the water fountain at Belk,” he said. His father, who was active in the NAACP, would say that one day that was going to change.

“We accepted where we were, but we were watching with great curiosity that changes that were pending,” he said, recalling the change in attitude when he saw a headline in the Charleston evening paper —“Segregation found unconstitutional.” Then “we realized how unhappy we were about the limitations.”

The Gantt family discussed events around the dinner table and the young Gantt read all the newspapers he could find at the library.

When the Supreme Court directed that desegregation be carried out with all deliberate speed and states took that to mean slow to never, “it was discouraging. It probably caused a certain paralysis, even in the African American community. What changed for me was when civil rights went from the pristine courts to a young preacher down in Montgomery, Ala., leading boycotts,” he said..

Students at Burke High took the example of Greensboro, N.C., students and began sit-ins at lunch counters, Gantt said.

“We couldn’t tell anybody past 19 years old,” he said. “We certainly couldn’t tell our parents. They found out when they were called to come get us out of jail,” which was a courtroom where they were held.

His mother was upset because she feared he had ruined his chance at a college education. His father, though, had “little wry smile.”

Gantt attended Iowa State but decided the cold didn’t agree with him and he wanted to practice architecture in the South. So he began applying at Clemson in 1961. Eventually he applied five times, and Clemson officials found reasons to turn him down although he was qualified. And the decisions always came at the last minute when no time existed to do what was needed.

“I was a little bit naive about how Clemson would react to my application. I did this on good faith that somebody would see this and admit me,” he said. When he sent his first letter of application to transfer from Iowa State, Clemson officials noted his qualifications were strong, but they needed a high school transcript. When that transcript from Burke High arrived, “the tone from Clemson changed.”

In 1963, Gantt filed a lawsuit to force Clemson to admit him. When he won the court case, South Carolina and Clemson knew they had lost the battle. State and Clemson officials decided that South Carolina was not going to be Mississippi, and his days at Clemson were peaceful.

He said at first he ate alone in the cafeteria and occasionally would hear epithets from fifth floor windows, but no students confronted him.

“I think the state patted itself on the back because it avoided the conflagration that happened in other states,” he said. “For me, it was a great thing because it was peaceful and I was not harassed by students. I was able to get an education.”

He said he figures South Carolina fought it as far as it could and was able to say to ardent segregationists, “We’ve done all we can.” But the college administration and businessmen probably said that they couldn’t allow his enrollment and study at Clemson “to become a mess.”

“Always in the back of my mind, they were more concerned about order than what the morality of integration was,” Gantt said, adding that many faculty, staff, and students silently approved his action but never publicly supported him.

Cox asked if the state’s actions may have been more peaceful because of the Mississippi turmoil.

Gantt said he didn’t know, but “when I saw James Meredith years later, I said ‘thank you.’”

When asked about unofficial protests on campus and the Rebel Underground, a newspaper that sprang up at the time, Gantt said, “Don’t underestimate the number of students who wanted to be on the winning side and were already thinking about what the South would be like with more diversity.”

He received a lot of quiet support although a small group of students were pointedly against his study at Clemson. But the students were warned by President Robert Edwards that they would be sent home if they caused problems. Gantt also was asked by the president not to be provocative. That surfaced when he planned to attend a dance. The president said he wasn’t sure that was wise because some white girl might ask him to dance. Gantt told the president he was going. He did, and he danced, he said.

“My first months of campus, I had a phalanx of SLED officers,” who tried to be unnoticed by dressing as college students, he said. One time some of his friends in architecture staged a fight with him to see if the officers were still alert. “Out of nowhere, these guys surfaced.”

With the peaceful entrance of Gantt to Clemson and subsequent African Americans enrolling without problems at other colleges, South Carolina never really had to face a moment of crisis as some states did, Cox said. But the state still hasn’t solved its racial problems.

“There’s progress,” Gantt said. “I don’t know that in my lifetime we will overcome the resistance by people who feel threatened by race. Sometimes moderation can be the worst thing that can happen when we’re trying to move the needle of change substantially.”

The state and the country need a deep conversation that probably has never happened. That discussion needs to center on race, economic equality, and the ability to move up the economic ladder.

“I keep hoping the next generation will recognize the importance of public service to help everyone move forward,” he said. “We’re not there yet. Although desegregation occurred, we’re still not quite integrated in our society.”

Learn more about Furman Univeristy’s Commemoration of 50 Years Since Desegregation furman.edu/50years.