On the Road with Peter Gwin

PETER GWIN REMEMBERS VIVIDLY the first time he experienced the thrill of sudden, bright-white clarity.

While on a Furman study abroad trip to the United Kingdom, he and some friends decided to visit the European continent. “We had some free time to travel, so we went to Rome,” he says. “We landed around 2 a.m. and got the classic taxi rip-off from the airport — it was raining, we paid way more than we should have, and got dropped in the middle of nowhere with no clue where we’d sleep that night.”

Wandering aimlessly through a dark labyrinth of alleys and unknown streets, Gwin and Co. suddenly happened upon Rome’s famous Trevi Fountain in all its resplendent glory. “It was spectacular — this massive golden fountain shimmering in the darkness, and we were the only ones there at the moment. It was like we had found buried treasure.

“That’s when I knew,” he says. “I recognized that feeling of discovery you get from the unexpected — turning a corner and finding a wonderful surprise.”

Today, almost three decades later, Gwin says those moments of blind, raw discovery happen frequently when he’s on assignment as a senior writer for National Geographic.

“I never know where they’re going to come from,” he says, then adds, “I live for those moments. In fact, I sort of tease my wife that I don’t have a drug problem, but I do have this travel problem. I’m addicted to those moments.”

They’ve occurred while he’s consorted with pirates in the Strait of Malacca. They’ve occurred during his investigation of the lost manuscripts of Timbuktu, his encounters with Shaolin Kung Fu masters, and his research into rhino poaching in southern Africa.

These are only a handful of the wide-ranging stories Peter Gwin ’88 has covered for the iconic, maize-rimmed monthly magazine. Inside its hallowed covers, National Geographic has for 125 years brought the world to our living rooms and captivated us with engaging stories married with stunning photography. Gwin has been part of that world since 2003.

Peter Gwin isn’t the only Furman graduate on the National Geographic payroll. Learn about the work Karen Buckley ’03 and Katy Wynn ’09 do at Geographic headquarters.

FOR ANY ASPIRING JOURNALIST, a writing post with such a revered publication has to be one of the plum jobs. The road to National Geographic was long and arduous, but Gwin says that it was well worth the effort.

For Gwin, the notion that a love of reading, literature and adventure could actually be parlayed into a career began to percolate during his high school days in Peachtree City, Ga. An English teacher introduced him to the works of Hemingway and Twain, and later he actually met another favorite, poet and novelist James Dickey (Deliverance). As a young man growing up in the South with a penchant for hunting and sports, Gwin was inspired by these and other writers whose robust literary styles were filled with tales of outdoor exploits.

Gwin’s liberal arts bent eventually drew him to Furman in what he says was an “intuitive” choice. He was an English major, wrote for The Paladin and was a contributor to and editor of the Echo, the student literary magazine. In addition to the United Kingdom, he also participated in the study away program to China.

While he focused on writing and literature, Gwin says, “All the classes I took — philosophy, world history, etc. — they were all important pieces of this quilt of learning. The great lesson of the liberal arts is that you learn how to learn about a variety of subjects and to think critically in the world, and that’s basically what I do for a living.

“When Geographic hands me a new assignment — from paleontology to indigenous cultures to astronomy, for example — those are not necessarily my specialties, but I feel fairly confident in finding the experts and translating their expertise into an engaging story for a general audience.”

As an undergraduate Gwin also had the chance to intern for the local NBC affiliate, where he gained experience in production research while working for PM Magazine, a nationally syndicated program. Again, he says, the experience was excellent preparation for his current work.

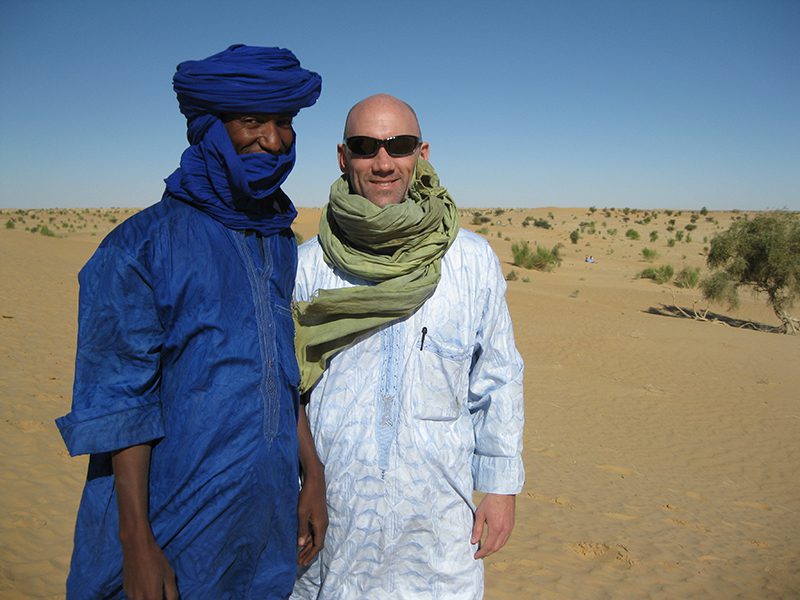

“For PM I would go to the Furman library to research the location the local hosts would be profiling and learn everything there is to know about New Zealand, for example. Now I’ll get an assignment about, say, the Tuareg ethnic group in the Sahara, and one of the first places I go is the Geographic library — which is amazing — and get every book I can on the subject.”

The prospect of working for National Geographic gained traction through Gwin’s contact with Nancy Seidule ’86 (now Hauth), a fellow English major who worked on the editorial staff at the magazine. She gave Gwin tips on how to land a job there — although it would be years before he could do so. In the meantime, he would amass a boatload of experiences that eventually led him to the holy grail of journalism.

AFTER GRADUATING from Furman and spending the summer traveling around the United States, Canada and Mexico, Gwin headed to Botswana in southern Africa. There he taught English through World Teach, an education program for developing countries. When he wasn’t teaching he hitchhiked around the region and sent dispatches about his travels to his hometown paper, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. He wrote about the Botswana election, the diamond industry and other events — but none of his stories were picked up.

This disappointment helped him learn one of the fundamental tenets of journalism: know your audience. “I didn’t make the stories particularly relevant to the people of Atlanta — or the United States for that matter,” he says. “There was no local hook” — a key detail the Journal’s editor shared with Gwin upon his return to the States. It was an important lesson, he says, and one that prepared him for the challenges that lay ahead.

With National Geographic still in his sights, and after fulfilling his one-year teaching commitment, Gwin moved to Washington D.C., and began freelancing for a range of small publications. Unfortunately, his first attempt to get a backdoor interview with National Geographic went awry. The story, which he laughs about now, includes an encounter with security.

Emerging from this episode jobless but relatively unscathed, Gwin sat down with a directory of Washington media outlets and methodically, painstakingly began making calls. He finally hit paydirt with Europe Magazine, whose editor-in-chief happened to pick up the phone that day.

Writing for Europe Magazine, Gwin says, helped groom him for National Geographic. He was part of a skeleton crew that produced the small monthly, which aimed to explain to its American audience what was then known as the European Community.

“It was a great place for me to start. Everyone had to wear lots of different hats, from researching and writing to tracking down sources and editing stringers,” says Gwin. “My first few months on the job the Soviet Union began to unravel and suddenly Europe was changing dramatically, and then came the Balkans wars and the rise of the single currency, and on and on. It was a great place for a young journalist to be.”

Gwin worked for the publication for about a decade, eventually rising to managing editor. But he never took his eyes off the prize.

He had a couple of chances to “audition” for National Geographic in the form of “legend writing tests” — legends being Geographic parlance for photo captions. Legend work, which combines artful writing and reporting, is the magazine’s time-honored entry-level position for writers. Gwin didn’t make the cut on his first try, but on his second attempt, in 2003, he got the job. It didn’t hurt that the test involved South Africa, about which he had firsthand knowledge.

Since that time, Gwin has researched and written several stories about far-flung people and places.

His “Battle for the Soul of Kung Fu” (March 2011) described the changing world of martial arts in China’s venerable Shaolin Temple. The story led to a Fulbright grant to return to China in 2012 to study aging Kung Fu masters.

Gwin filmed dozens of elderly masters telling their life stories. The men, he says, were like walking time capsules, with their 70- to 80-year perspectives on history. “They have witnessed an epic sweep of Chinese history, from the warlord era to the Japanese occupation, the Cultural Revolution, and now the opening.” Gwin, forever trawling for material, says China is fertile ground for many follow-on stories, and he hopes to channel his research into a documentary at some point.

Another assignment took him to Malaysia, which borders the Strait of Malacca, a chokepoint linking the Indian and Pacific oceans — and a place pirates have haunted for centuries. There he interviewed one of 10 prisoners captured by police following the 2005 hijacking of the Nepline Delima, a tanker that carried seven tons of diesel fuel worth $3 million.

“Dark Passage” (October 2007) chronicled the heist and the exploits of machete-wielding pirates with names like Jhonny Batam and Beach Boy. The pirates actually showed Gwin how to commandeer a ship by shimmying up the stern with a bamboo pole.

The article caught the attention of filmmaker Michael Mann, producer of The Aviator and director of Heat, The Insider and Collateral, among others. He and Gwin met to discuss making a feature film about modern piracy and setting the film in the region. Gwin says the film is in the early stages of development and is thrilled that Mann, a stickler for detail, is at the helm.

NO STRANGER to edgy, dark and downright dangerous places, Gwin has also covered the Sahara since 2005 when he traveled to Niger to report on an archaeology dig in the desert. That led to an assignment covering a rebellion by Niger’s Tuareg population, the famous “blue men of the desert.” He and a photographer embedded with a band of Tuareg rebels in the Aïr Mountains, where they navigated mine-littered byways and spent much of their time scanning the skies for Niger military helicopters hunting the rebels. As he says, “When you’re crossing long stretches of massive sand dunes, there really isn’t any place to hide.”

The story of the Tuareg led him to Timbuktu, the ancient desert city in neighboring Mali. His January 2011 article, “The Telltale Scribes of Timbuktu,” was selected for inclusion in “Best American Travel Stories 2012” and earned the Lowell Thomas Award from the Society of American Travel Writers for best foreign travel story. The judges praised Gwin’s work, describing his writing as “so filled with atmosphere and memorable people it might have been written by John le Carré. The name itself is a veritable synonym for a place so far removed it epitomizes the other side of the world. And the writer takes us there — with facts, history and unforgettable descriptions.”

Gwin’s article begins with how Islamic terrorists over the years had established bases in Northern Mali’s vast desert wilderness and were kidnapping Westerners and holding them for ransom, a situation that had practically strangled tourism in the city. It then moves elegantly into complex sub-stories about ancient and cherished fragments of books, letters and manuscripts recovered from caravans or housed in private libraries that remained after the Moroccan army looted and dispersed the city’s great libraries in the 16th century.

Gwin also managed to weave in threads of romance by telling the story of a Green Beret sent to Timbuktu to train Malian soldiers to fight the terrorists. The serviceman met a local woman, fell in love and converted to Islam so that they would be allowed to marry, although in the end the marriage did not take place.

Through the years — and numerous visits — Gwin has developed close ties with people in the region. “Watching what’s happening there is really painful because Timbuktu and the rest of northern Mali have been taken over by the extremists,” he says. “Now a branch of Al Qaeda controls the area. It’s a tragedy. A lot of the people I know have had to flee. They’ve lost everything — homes, businesses, livestock. Others are being forced to live under an extreme interpretation of Sharia. In some cases the terrorists have forced their sons to join them.”

Gwin says he’s eager to get back to the region, but gaining access to Timbuktu and the surrounding occupied areas is highly dangerous. “Not just for me, but for any of my friends there who would try to help me,” he says. “It’s just not worth the risk.”

RISK IS SOMETHING both Gwin and his wife, Cathy, have adjusted to. “My wife, in addition to being the love of my life, has been incredibly supportive about my assignments. She’s never flinched, never once,” he says. “I’ll come home and say, ‘Honey, I’m going away to do a story on pirates!’ She’s never freaked out or told me not to go. We have this understanding that I won’t do anything crazy. On the other hand, she’s never asked me to define what crazy is.”

Gwin, the father of two young girls, gets the “How dangerous is your job?” question often. The unglamorous truth, he says, is that the dangers that keep him awake before a trip are things that people don’t think about, such as weird diseases you might contract in a place where there’s little healthcare, or car accidents that happen as a result of poorly maintained roads or “hellhound” drivers.

One of his recent stories, “Rhino Wars” (March 2012), took him deep into the Zimbabwean bush to follow a game ranger and his recruits as they hunted for rhinoceros poachers. Tagging along on a nighttime patrol, Gwin heard gunshots reverberating in the darkness — and suddenly found himself joining in hot pursuit of the suspected poachers.

Poachers hunt and kill rhinos for their prized horns, which on the Asian black market can rival the price of gold or cocaine, according to Gwin. The coveted horns are ground up and used for traditional Asian medicines that some believe can help cancer patients, reduce fevers, improve circulation and prevent strokes, among other things. For the story Gwin interviewed an incarcerated rhino poacher, a user of Asian medicines, members of the medical community, and a South African farmer who raises rhinos to sustainably (and humanely) harvest rhino horn.

Considering the conservation and cultural issues surrounding rhino horn, the story opened the door to the complex nature of the subject. Says Gwin, “At first I thought it was a straightforward poaching story, but the deeper I got into it the more I began to realize it was much more than just one magazine story.” Since the story came out last spring, Gwin has continued to research the subject and follow many of the characters he profiled in the magazine for a book to be published by National Geographic Books. As rhino poaching reaches “epidemic” proportions, with 668 rhinos slaughtered in South Africa alone last year, the timing for the tome couldn’t be better.

GWIN IS CLEARLY GRATEFUL for the opportunities National Geographic has given him to see the world and meet fascinating people, and for the meticulous planning that permeates each article and each issue.

Gwin recalls one of the earliest projects he contributed to for National Geographic: “It was one of those maps that fall in your lap when you open up the magazine. The work that goes into those things is unbelievable.” Gwin and a team of experts crafted a map supplement depicting Native American history. Cartographers, Native American leaders, historians, artists and fact checkers collaborated on the project, which took nearly two months to complete. “This is the kind of thing I would have taped up in my bedroom when I was a kid,” says Gwin. “The thought of that map helping to shape some kid’s sense of the world and spark his or her imagination is very satisfying.”

Working at National Geographic has helped Gwin appreciate his chance to be part of the magazine’s heritage and legacy. “Occasionally I’ll get to meet some of our retired writers and photographers, who always have amazing stories about exploring the Amazon or the Himalaya in the 1940s and ’50s. The place is steeped in the lore of exploration.”

Respected and lauded for its storytelling, craftsmanship and attention to detail, National Geographic has earned the trust of generations of readers. Gwin points out that almost 70 years ago, “[General] Eisenhower came to Geographic for maps when planning the Allied invasion of France. The badge of National Geographic is a good one and has a long history.”

It’s a badge that Peter Gwin is proud to wear.

Tina Underwood lives in Greenville and writes for Furman’s Office of Marketing and Public Relations. This article appeared in the Winter 2013 issue of Furman magazine.